- Home

- Steven Cojocaru

Glamour, Interrupted Page 4

Glamour, Interrupted Read online

Page 4

But there was no way I was going to ask Mr. and Mrs. Cojo for a kidney, and my sister’s compatibility hadn’t been determined yet. My first concern was for my sweet, gentle, delicate parents. I can’t risk operating on people in their seventies, I thought. Under no circumstances will I put my mother and father in danger.

All of these thoughts and anxieties haunted me through the fall, and the stress was wreaking havoc on my body. I was wired from guzzling diet soda day and night, and suffered from an insomnia that left me hypnotized by infomercials for Victoria Principal’s kelp masks until dawn. I was at a standstill, unsure how to even start this whole process of announcing the news to my intimates and going begging for a kidney. I couldn’t do it alone. I needed someone to support me and be my cushion as I faced the most difficult conversation I might ever have with my parents. I went back and forth and back and forth until my heart finally pulled me toward one of the safest havens I had: My best friend Abby.

Abby thinks I’m from another planet and loves me anyway. I often question whether my ultra-straightlaced friend is the secret adopted love child of Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly. On weekends she makes sandwiches for the homeless. I spend my free time getting my epidermis varnished at the dermatologist’s. She knits, I cocktail. Despite being completely, totally, utterly different, Abby has always been my lighthouse, my anchor.

When I moved to Los Angeles, Abby was my first friend, the woman who knocked me into shape and taught me how to take care of myself. When I was growing up, my mother never taught me how to do household things. I was the male heir in an Eastern European family, which meant I was practically a demigod. It’s such a medieval system: The daughter (i.e., my sister Alisa) is taught to cook and sew and the son (i.e., Me) isn’t even allowed to tie his own tennis shoes.

This princely upbringing would come back and bite me in the derriere when I got the keys to my first Hollywood apartment. Within a week, surgical masks were required for any soul with the wherewithal to brave the delightful smells of moldy lasagna and my leaning tower of dirty socks. Abby made it through the doorway and immediately appointed herself Head of Housekeeping. She taught me what a flat sheet was. She sternly informed me that you couldn’t make a suit out of steel wool. And, the worst humiliation of all, she took my toilet-cleaning virginity away from me. But she was also there for me during all the tough, rough times, when I was down and out—poor, lonely, rejected, and wearing really bad clothes.

Abby was now living in New York, where she developed television projects like Comedy Central’s Kenny vs. Spenny, and telling her about my disease would involve bonus miles. In October, when I was in town, I invited her out to dinner at an Italian trattoria: I chose Italian, because I felt if you were going to go down you might as well do it while mainlining spaghettini puttanesca and ossobuco alla Milanese and five heaping helpings of paper-thin melt-in-your-mouth imported prosciutto—not to mention gallons of chianti. I was tempting fate by consuming alcohol, considering that my put-upon kidneys could barely process a green tea–pomegranate bran muffin anymore.

But once we were seated at the table, I couldn’t face it. Once I tell Abby, this is going to be real, I thought, as we ate. It won’t be a bad dream anymore. So we finished dinner without a word from me. And then I was going to tell her on the walk back home to her apartment, but I still wasn’t ready. I kept putting it off. It was an unseasonably warm evening, and as we walked the quiet streets to her Upper East Side apartment, I was about to spontaneously combust from the tension. I kept telling myself, Tell her now! But then a desperate plea would echo through my brain: No—twenty more minutes of freedom! Please! Twenty more minutes of life as I know it!

When we arrived at her apartment I realized that I couldn’t buy any more time. Her studio apartment was a maze of cardboard boxes and bubble wrap: She had only recently moved in, and there was no furniture. We sat down on orange crates and finally I blurted out: “Abby, I have some bad medical news about me…. I’ve been diagnosed with kidney disease.”

Abby’s breath seemed to stop. I was so struck by the look in her eyes that I couldn’t even hear her response: Her entire being seemed to ache for me. She came over and put her arms around me and held me as I began to sob. For the first time in months—maybe even a lifetime—I invited the wounded creature inside of me to come outside.

Abby, always the caretaker, soon composed herself. I was still in pieces but she was already stoicly contemplating a plan of attack. “What’s the first step you need to take?” she asked.

“I need to have a kidney transplant,” I told her. “I need to find a kidney donor.”

I rattled on, explaining what the disease is and what my options were, as she listened quietly. When I was done, Abby spoke up. “I’ll give you a kidney,” she said. “I don’t even need to think twice about it.”

I traveled past mere garden-variety shock and went straight into the stratosphere of amazement. I was so moved to discover that Abby was capable of so much compassion and generosity. That’s what sent my circuits racing. Even if she was being a really loving friend and just saying it to comfort me, her words warmed my very being.

We went outside because we needed air and sat on the stoop of her building for a long time. We talked about all the issues—my concerns about my parents, my fears about losing my job, what a transplant would mean to my health. And sensible Abby immediately began making plans.

“We are going to take care of this,” she said. And with these words suddenly I was not alone in the cage with my disease anymore. Suddenly, I was part of a “we,” and that “we” was so nourishing to me: It gave me the greatest sense of relief.

I left Abby to ponder her offer. It still hadn’t really hit me that she could possibly be my donor. But she never wavered from that first conversation. It was all very black and white to her, and I was relieved to heap this mountain of stress on someone. She had the clarity, and I clung to her. I still didn’t know what the bigger picture would ultimately end up being: I needed to talk to my family, to consider my sibling as a donor. But, despite not knowing how it was going to end up, who was going to ultimately be giving me a kidney, we took the first steps toward finding out Abby’s compatibility. Could she possibly be The One?

While Abby was undergoing the first compatibility tests in New York, I practically had a cot at Cedars-Sinai. My kidneys were failing, and my doctors were doing everything they could to sustain their life expectancy: Nearly every day I was being called into the hospital for some sort of test or shot. There were nonstop blood draws and epogen shots for anemia. I was pumped with pills to control my potassium, calcium, and blood sugar levels: When your kidneys are failing, everything in your body fails with them so every single neuron had to be inspected. The doctors were obsessed with my urine output: For one particularly gruesome test, I had to collect every drop of urine over a 24-hour period and carry it around with me in a plastic container surrounded by icepacks that I hid in my napsack. And I had made a new friend, gout.

With so many jaunts to the hospital, it was growing impossible to conceal the truth from my employers at Entertainment Tonight. In mid-November, I took the Kidney Confession Tour to the Paramount Lot, where I summoned my bosses—Linda Bell Blue, the executive producer; Janet Annino, then co-executive producer on ET; and Terry Wood, who oversees all of CBS/Paramount’s domestic television. “I need to tell you something,” I told Janet, “but it needs to be somewhere private.”

“How private?” she asked.

“I mean private, think Area 51, no lip-readers in sight,” I said.

It’s not easy to find privacy in the offices of Entertainment Tonight: We looked in one conference room, and then another, but there were always people around.

“Why don’t we go to New York?” I suggested.

If you’ve watched Ghost or Seinfeld, you’ve seen the New York I’m talking about: It’s a perfect replica of an old New York street, permanently erected on Paramount’s back lot. Lined up along t

he tree-shaded lane are dozens of rowhouses and musty storefronts. Look up and in the distance you’ll see palm trees. It is surreal: New York City, California 90038.

I sat on the steps of a fake brownstone, in the warm fall sunshine, with Janet, Linda, and Terry, and I told them what was going on. “I don’t know what I’m going to do with work; how this is going to affect my career,” I said.

“No matter what happens, we’re behind you,” Terry assured me.

Eternally a producer, Linda immediately took charge of my transplant; “We’ll get you in touch with some good doctors,” she said. “We’re going to make sure you get the best care.”

The four of us sat there weeping. I was surprised: I’d expected anyone in their positions to see me as flawed, to say, Take your useless kidneys and get off the lot! Instead, surrounded by these strong, extraordinary women, I knew I was part of a unit. These powerhouses could produce anything, and they’d decided to take me on as their next blockbuster project.

As we sat there drying our eyes, a tour went by with a dozen tourists walking through the set. One woman eyed us and then ripped herself away from the group to come stand in front of us. She stared at me and then blurted out: “Are you Cojo?!”

“Yes,” I replied. “Hi!”

Beside me, Linda was already on the phone with a doctor. I was still drying the tears off my face. Janet and Terry were hugging me. But the woman in front of me had more important concerns: “What do you think of my outfit?” she bubbled.

The news within ET began to take on a life of its own. A television interview with Mary Hart was in the works and a press release had been drafted. I had to scrounge up the courage to be so public with my illness, but I refused to spend my life in hiding: Both in my personal life, and also with my high-visibility job. Once this van was moving, there was no turning back. I was going public. It was too far gone. I wasn’t going to go to Cedars-Sinai in giant sunglasses and a poly-cotton burqa forever. And it was time to tell my family, before they found out from someone else.

I’d played the scene of telling my parents in my head over and over and over again. I’d built it up to be this monumental event. I would fly them out to California. I toyed with the idea of telling them over kosher Chinese, but that seemed frivolous: I just wanted them in my living room, to somehow tell them straight on, no bells, no whistles. I imagined their arms around me and our stereophonic group weep-a-thon; they would soon break away and start praying to various deceased relatives.

But when the moment came, it wasn’t the way I had planned. By the end of November, my bosses and I had concurred that it wasn’t practical to contain my secret any longer, and my ET interview was about to air. My parents were on vacation in Israel for a month, visiting relatives. I felt nauseous as I picked up the phone to tell them. I will always feel guilty about not telling them in person, but at least, I thought, they were with family so they would have great support and comfort enveloping them.

According to Cojocaru Family Law, you don’t make a call across an ocean, two seas, and a desert unless you’ve got a pregnancy to announce or really bad news. I could tell my mother was taken aback by the sound of my voice.

“What? What’s going on?”

“Mom, I have some news,” I said. My heart wasn’t palpitating anymore. In the moment, I turned strong and laid out my concerns. “It’s going to sound bad, but listen to me…everything will be OK! You have to promise me that whatever I say to you you can’t start with the screaming and hysteria. I need you to be calm.”

And my mother, to her infinite credit, did stay calm. “OK, I’m listening,” she said.

“I went to a doctor, had some tests, and something is wrong with my kidneys,” I said, slowly.

I heard a gasp on the other end of the line. “What’s wrong?!” She asked.

I didn’t tiptoe. “Listen, I have to have a kidney transplant,” I said. “But my doctor says it’s very treatable, very fixable. It’s not as scary as it sounds.”

I couldn’t hear a sound through the phone except for her labored breathing. “Oh my God,” she whispered. “Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God. This can’t be. Where are you? I’m coming to you.”

“No. Stay with your family. It’s going to be in the news, and you are so much better off there. You’ll have time to think and collect yourself.”

“The news?!” she cried. “Are you crazy! Don’t tell anyone! It’s private!”

That I was going public seemed to send my mother over the top. It’s understandable: She grew up in Holocaust Romania, where if you said the wrong word you were arrested and never seen again. You didn’t air your laundry in public, not just because it wasn’t polite, but also because you could end up rotting in the bottom of a pit in the woods.

“I’m not going to hide,” I said. “Mother, I can’t exactly go on vacation for a year, I can’t pretend I’m going to Italy to study abroad. People know me.”

We stayed on the phone for an hour, much of it simply not talking. I broke down. She broke down. When I hung up the phone, I was surprised by the catharsis that I felt: It hadn’t been as bad as I thought. My mother may have been shocked, but I’d heard something in her voice that sounded more like strength. Now, the stage was set. I had told my parents, my friends and work, and I even had a potential donor; I was leaving Denialville and shipping my baggage to a new zip code.

When I got to the studio the day of my first public interview about my disease, the crew still had no idea why I was being interviewed. And when the interview with Mary Hart was over, everyone’s jaws were hanging open. It was out there. I felt buoyed, and a little high, almost elated. I could almost see the relief oozing out of my pores. In the days that followed, a media frenzy ensued: Suddenly my kidneys were the most famous internal organs in America.

I started getting E-mails from around the world, coming from as far away as Greece, Singapore, Australia, the Philippines, and England. There were thousands of E-mails—printed out, the stack of messages was a foot tall—and I read them all. They sustained me.

From a family also with PKD, I wish you the best. I lost my mother, grandmother, and two uncles to this disease, and now one of two sisters has it. Luckily I do not; however, I know the effects and problems you must be going through. My mom had a double transplant, liver and kidney, and we lost her after forty-two days. But she was sixty-nine, and you are young, otherwise healthy, and, I believe, too full of life to let this get the best of you. Keep your head up and live every day to the fullest. You will be in my prayers.

Cojo! Wow. Last night I tuned in to ET to get my daily dose of celebrity news. When I heard about your kidney, I couldn’t stop watching the show. I’ve had kidney disease since I was born and I was on different forms of dialysis for three years. I think it is so inspiring and brave of you to come out and let people know what kidney disease and transplants are all about. I have provided my E-mail, should you ever need a buddy to talk to.

Those E-mails were gifts that went straight to my heart. You can’t imagine how it feels to know that you are the recipient of mass affection, that thousands of people with pure hearts are praying for you, lighting candles, wishing you well. I could almost feel them healing me.

I knew that going public with my disease would have some kind of impact, but only when I started receiving these E-mails did I really understand what a difference I might be able to make. When I read their letters and heard their voices in my head, I suddenly understood that I could inspire people to do something tangible about kidney disease.

Cojo, After I saw your story on ET I was so touched by it that I filled out the donor card on my ID. May God bless you.

I had made contact. It amazed me that just by talking about my disease, in the most simplistic of terms, I was capable of moving people into action.

In early December, a tube of Abby’s blood took a flight from New York to Los Angeles and straight to Cedars-Sinai for testing. I fixated on her blood practically every minute of that we

ek, while we waited for the test results. That week, Entertainment Tonight sent me to visit the “death headquarters” of Academy Award–winning makeup artist Matthew Mungle, designer of the dead bodies on CSI. Over the course of three hours, he made me over as a corpse in latex and fake blood. Afterward, I stared at a deathly visage of myself in the mirror and couldn’t help but shiver. Abby’s blood had to be a match.

When the call came, three days later, I was still picking latex out of my nostrils. “I have very good news, Steven,” Dr. Jordan said. I could hear the smile in his voice. “Abby’s a match.”

“She’s a match? Really?” I was laughing and crying at the same. My head was spinning so quickly I almost felt it detach and fly off my body. I hung up and called my parents.

I screamed into the phone before my mother even had a chance to say hello. “It’s a match!” I screamed. “It’s a match!”

I could practically hear my parents doing the cha-cha on top of the dining room table in Montreal. “I’ve been praying and praying! Every rabbi in Montreal has been praying!” my mother cried. I could hear her knocking on something in the background. “Touch wood, I am so happy. I love Abby!”

The next call was to Abby. “We’re doing this, aren’t we?” she said, when she heard my shrieking voice on the other end of the line. She didn’t sound the least bit frightened.

Abby made plans to come to Los Angeles for the final tests at the end of December and if all went well, she’d move in with me until the operation in mid-January. The transplant that had always seemed so intangible was now just a matter of weeks away.

I had one final appearance on the Today show before the end of the year. I flew out to New York just before the holidays. It was my usual It’s Cojo Time, a frothy fun segment showing the hottest products worn by celebrities: cellulite-busting jeans, J. Lo’s monogrammed panties (at the time, very au courant) and Pamela Anderson’s soda pop–top eco-friendly handbags.

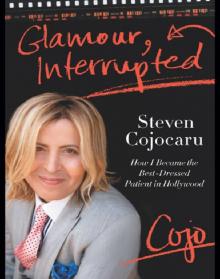

Glamour, Interrupted

Glamour, Interrupted